Cummings

Guides Home..|..Contact

This Site

.

.

Notes

Compiled by Michael J. Cummings...©

2005

Revised

and Enlarged in 2010

Type

of Work

.

......."Ode

on a Grecian Urn" is a romantic ode, a dignified but highly lyrical (emotional)

poem in which the author speaks to a person or thing absent or present.

In this famous ode, Keats addresses the urn and the images on it. The romantic

ode was at the pinnacle of its popularity in the nineteenth century. It

was the result of an author’s deep meditation on the person or object.

.......The

romantic ode evolved from the ancient Greek ode, written in a serious tone

to celebrate an event or to praise an individual. The Greek ode was intended

to be sung by a chorus or by one person to the accompaniment of musical

instruments. The odes of the Greek poet Pindar (circa 518-438 BC) frequently

extolled athletes who participated in athletic games at Olympus, Delphi,

the Isthmus of Corinth, and Nemea. Bacchylides, a contemporary of Pindar,

also wrote odes praising athletes.

.......The

Roman poets Horace (65-8 BC) and Catullus (84-54 BC) wrote odes based on

the Greek model, but their odes were not intended to be sung. In the nineteenth

century, English romantic poets wrote odes that retained the serious tone

of the Greek ode. However, like the Roman poets, they did not write odes

to be sung. Unlike the Roman poets, though, the authors of 19th Century

romantic odes generally were more emotional in their writing. The author

of a typical romantic ode focused on a scene, pondered its meaning, and

presented a highly personal reaction to it that included a special insight

at the end of the poem (like the closing lines of “Ode on a Grecian Urn”).

Writing

and Publication Dates

......."Ode

on a Grecian Urn" was written in the spring of 1819 and published later

that year in Annals of the Fine Arts, which focused on architecture,

sculpture, and painting but sometimes published poems and essays with themes

related to the arts.

Structure

and Meter

......."Ode

on a Grecian Urn" consists of five stanzas that present a scene, describe

and comment on what it shows, and offer a general truth that the scene

teaches a person analyzing the scene. Each stanza has ten lines written

in iambic pentameter, a pattern of rhythm (meter) that assigns ten syllables

to each line. The first syllable is unaccented, the second accented, the

third unaccented, the fourth accented, and so on. Note, for example, the

accent pattern of the first two lines of the poem. The unaccented syllables

are in lower-cased blue letters, and the accented syllables are in upper-cased

red letters.

thou

STILL..|..un

RAV..|..ished

BRIDE..|..of

QUI..|..et

NESS,

thou

FOS..|..ter

CHILD..|..of

SI..|..lence

AND..|..slow

TIME

Notice that each line has

ten syllables, five unaccented ones in blue and five accented ones in red.

Thus, these lines—like the other lines in the poem—are in iambic pentameter.

Iambic

refers to a pair of syllables, one unaccented and the other accented. Such

a pair is called an iamb. "Thou STILL" is an iamb; so are "et NESS"

and "slow TIME." However, "BRIDE of" and "FOS ter" are not iambs because

they consist of an accented syllable followed by an unaccented syllable.

Pentameter—the first syllable of which is derived from the Greek word for

five—refers

to lines that have five iambs (which, as demonstrated, each have two syllables).

"Ode on a Grecian Urn," then, is in iambic pentameter because every line

has five iambs, each iamb consisting of an unaccented syllable followed

by an accented one. The purpose of this stress pattern is to give the poem

rhythm that pleases the ear.

Situation

and Setting

.......In

England, Keats examines a marble urn crafted in ancient Greece. (Whether

such an urn was real or imagined is uncertain. However, many artifacts

from ancient Greece, ones which could have inspired Keats, were on display

in the British Museum at the time that Keats wrote the poem.) Pictured

on the urn, a type of vase, are pastoral scenes in Greece. In one scene,

males are chasing females in some sort of revelry or celebration. There

are musicians playing pipes (wind instruments such as flutes) and timbrels

(ancient tambourines). Keats wonders whether the images represent both

gods and humans. He also wonders what has occasioned their merrymaking.

A second scene depicts people leading a heifer to a sacrificial altar.

Keats writes his ode about what he sees, addressing or commenting on the

urn and its images as if they were real beings with whom he can speak.

.

.

Ode

on a Grecian Urn

By John Keats

End-Rhyming Words Are

Highlighted

Stanza 1

Thou still unravish’d bride

of quietness,

Thou foster-child

of silence and slow time,

Sylvan historian, who canst

thus express

A flowery tale more

sweetly than our rhyme:

What leaf-fring’d legend

haunts about thy shape

Of deities or mortals,

or of both,

In Tempe

or the dales of Arcady?

What men or gods

are these? What maidens loth?

What mad pursuit?

What struggle to escape?

What pipes

and timbrels? What wild ecstasy?

Stanza 2

Heard melodies are sweet,

but those unheard

Are sweeter; therefore,

ye soft pipes, play on;

Not to the sensual ear,

but, more endear’d,

Pipe to the spirit

ditties of no tone:

Fair youth, beneath the

trees, thou canst not leave

Thy song, nor ever

can those trees be bare;

Bold

Lover, never, never canst thou kiss,

Though winning near the

goal—yet, do not grieve;

She cannot fade,

though thou hast not thy bliss,

For ever

wilt thou love, and she be fair!

Stanza 3

Ah, happy, happy boughs!

that cannot shed

Your leaves, nor

ever bid the Spring adieu;

And, happy melodist, unwearied,

[un WEER e ED]

For ever piping songs

for ever new;

More happy love! more happy,

happy love!

For ever warm and

still to be enjoy’d,

For ever

panting, and for ever young;

All breathing human passion

far above,

That leaves a heart

high-sorrowful and cloy’d,

A burning

forehead, and a parching tongue.

Stanza 4

Who are these coming to the

sacrifice?

To what green altar,

O mysterious priest,

Lead’st thou that heifer

lowing at the skies,

And all her silken

flanks with garlands drest?

What little town by river

or sea shore,

Or mountain-built

with peaceful citadel,

Is emptied

of this folk, this pious morn?

And, little town, thy streets

for evermore

Will silent be; and

not a soul to tell

Why thou

art desolate, can e’er return.

Stanza 5

O Attic shape! Fair attitude!

with brede

Of marble men and

maidens overwrought,

With forest branches and

the trodden weed;

Thou, silent form,

dost tease us out of thought

As doth eternity: Cold Pastoral!

When old age shall

this generation waste,

Thou

shalt remain, in midst of other woe

Than ours, a friend to man,

to whom thou say’st,

“Beauty is truth,

truth beauty,”—that is all

Ye know

on earth, and all ye need to know.

.

Summary and Annotations

Stanza 1

.......Keats

calls the urn an “unravish’d bride of quietness” because it has existed

for centuries without undergoing any changes (it is “unravished”) as it

sits quietly on a shelf or table. He also calls it a “foster-child of silence

and time” because it is has been adopted by silence and time, parents who

have conferred on the urn eternal stillness. In addition, Keats refers

to the urn as a “sylvan historian” because it records a pastoral scene

from long ago. (“Sylvan” refers to anything pertaining to woods or forests.)

This scene tells a story (“legend”) in pictures framed with leaves (“leaf-fring’d”)–a

story that the urn tells more charmingly with its images than Keats does

with his pen. Keats speculates that the scene is set either in Tempe or

Arcady. Tempe is a valley in Thessaly, Greece–between Mount Olympus and

Mount Ossa–that is favored by Apollo, the god of poetry and music. Arcady

is Arcadia, a picturesque region in the Peloponnesus (a peninsula making

up the southern part of Greece) where inhabitants live in carefree simplicity.

Keats wonders whether the images he sees represent humans or gods. And,

he asks, who are the reluctant (“loth”) maidens and what is the activity

taking place?

Stanza 2

.......Using

paradox and oxymoron to open Stanza 2, Keats praises the silent music coming

from the pipes and timbrels as far more pleasing than the audible music

of real life, for the music from the urn is for the spirit. Keats then

notes that the young man playing the pipe beneath trees must always remain

an etched figure on the urn. He is fixed in time like the leaves on the

tree. They will remain ever green and never die. Keats also says the bold

young lover (who may be the piper or another person) can never embrace

the maiden next to him even though he is so close to her. However, Keats

says, the young man should not grieve, for his lady love will remain beautiful

forever, and their love–though unfulfilled–will continue through all eternity.

Stanza 3

.......Keats

addresses the trees, calling them “happy, happy boughs” because they will

never shed their leaves, and then addresses the young piper, calling him

“happy melodist” because his songs will continue forever. In addition,

the young man's love for the maiden will remain forever “warm and still

to be enjoy’d / For ever panting, and for ever young. . . .” In contrast,

Keats says, the love between a man and a woman in the real world is imperfect,

bringing pain and sorrow and desire that cannot be fully quenched. The

lover comes away with a “burning forehead, and a parching tongue.”

Stanza 4

.......Keats

inquires about the images of people approaching an altar to sacrifice a

"lowing" (mooing) cow, one that has never borne a calf, on a green altar.

Do these simple folk come from a little town on a river, a seashore, or

a mountain topped by a peaceful fortress. Wherever the town is, it will

be forever empty, for all of its inhabitants are here participating in

the festivities depicted on the urn. Like the other figures on the urn,

townspeople are frozen in time; they cannot escape the urn and return to

their homes.

Stanza 5

.......Keats

begins by addressing the urn as an “attic shape.” Attic refers to Attica,

a region of east-central ancient Greece in which Athens was the chief city.

Shape, of course, refers to the urn. Thus, attic shape is an urn that was

crafted in ancient Attica. The urn is a beautiful one, poet says, adorned

with “brede” (braiding, embroidery) depicting marble men and women enacting

a scene in the tangle of  forest

tree branches and weeds. As people look upon the scene, they ponder it–as

they would ponder eternity–trying so hard to grasp its meaning that they

exhaust themselves of thought. Keats calls the scene a “cold pastoral!”–in

part because it is made of cold, unchanging marble and in part, perhaps,

because it frustrates him with its unfathomable mysteries, as does eternity.

(At this time in his life, Keats was suffering from tuberculosis, a disease

that had killed his brother, and was no doubt much occupied with thoughts

of eternity. He was also passionately in love with a young woman, Fanny

Brawne, but was unable to act decisively on his feelings–even though she

reciprocated his love–because he believed his lower social status and his

dubious financial situation stood in the way. Consequently, he was like

the cold marble of the urn–fixed and immovable.) Keats says that

when death claims him and all those of his generation, the urn will remain.

And it will say to the next generation what it has said to Keats:

“Beauty is truth, truth beauty.” In other words, do not try to look beyond

the beauty of the urn and its images, which are representations of the

eternal, for no one can see into eternity. The beauty itself is enough

for a human; that is the only truth that a human can fully grasp. The poem

ends with an endorsement of these words, saying they make up the only axiom

that any human being really needs to know. forest

tree branches and weeds. As people look upon the scene, they ponder it–as

they would ponder eternity–trying so hard to grasp its meaning that they

exhaust themselves of thought. Keats calls the scene a “cold pastoral!”–in

part because it is made of cold, unchanging marble and in part, perhaps,

because it frustrates him with its unfathomable mysteries, as does eternity.

(At this time in his life, Keats was suffering from tuberculosis, a disease

that had killed his brother, and was no doubt much occupied with thoughts

of eternity. He was also passionately in love with a young woman, Fanny

Brawne, but was unable to act decisively on his feelings–even though she

reciprocated his love–because he believed his lower social status and his

dubious financial situation stood in the way. Consequently, he was like

the cold marble of the urn–fixed and immovable.) Keats says that

when death claims him and all those of his generation, the urn will remain.

And it will say to the next generation what it has said to Keats:

“Beauty is truth, truth beauty.” In other words, do not try to look beyond

the beauty of the urn and its images, which are representations of the

eternal, for no one can see into eternity. The beauty itself is enough

for a human; that is the only truth that a human can fully grasp. The poem

ends with an endorsement of these words, saying they make up the only axiom

that any human being really needs to know.

.

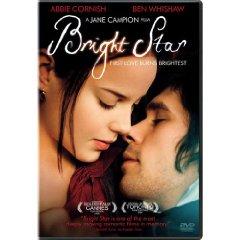

Bright Star

.

Award-Winning Film About Keats and

Fanny Brawne

(Rated PG)

.

.......Now

available at Amazon.com is Bright

Star, a DVD centering on the soulful love affair between John Keats

and Fanny Brawne when he was at the height of his poetic powers and in

the throes of disease that ended his life when he was only twenty-five.

Amazon.com says it is "rich, sensuous, quietly thrilling," a film to be

added "to the very short list of admirable films about writers." The review

continues as follows:

.......The

movie, set during his last several years, focuses on his playful friendship

with and evolving love for Fanny Brawne (Abbie Cornish), the independent-minded

young woman who lived next door in Hampstead Village and was, in her own

fashion, an artistic spirit. Completing an ineffably fraught constellation—not

exactly a romantic triangle—is Keats's host Charles Armitage Brown (Paul

Schneider), who loves, esteems, and regards Keats with both pride and envy,

and engages in an unstated rivalry for Fanny. All three performances are

superb, with Whishaw adding to his gallery of artist figures (the olfactorily

obsessed murderer in Perfume, one of the Bob Dylans in I'm Not There),

and Cornish and Schneider taking top acting honors for 2009. As in Campion's

The Piano, others are party to the central story, and they have identities,

personalities, and claims to intelligence and understanding that we appreciate

without having it announced in dialogue. Kerry Fox (redheaded wild girl

of Campion's An Angel at My Table nearly two decades ago) evokes Fanny's

mother with a few brushstrokes, and Fanny's young sister and brother are

watchful presences and de facto co-conspirators in the courtship. In addition,

Bright Star is the rare period movie to convey—without being insistent—what

it was like to be alive in another era, the nature of houses and rooms

and how people occupied them, the way windows linked spaces and enlarged

people's lives and experiences, how fires warmed as the milky English sunlight

did not. And always there is an aliveness to place and weather, the creak

of boardwalk underfoot and the wind rustling the reeds as lovers walk through

a wetland. Poetry grows from such things; at least, Jane Campion's does.—Richard

T. Jameson .......The

movie, set during his last several years, focuses on his playful friendship

with and evolving love for Fanny Brawne (Abbie Cornish), the independent-minded

young woman who lived next door in Hampstead Village and was, in her own

fashion, an artistic spirit. Completing an ineffably fraught constellation—not

exactly a romantic triangle—is Keats's host Charles Armitage Brown (Paul

Schneider), who loves, esteems, and regards Keats with both pride and envy,

and engages in an unstated rivalry for Fanny. All three performances are

superb, with Whishaw adding to his gallery of artist figures (the olfactorily

obsessed murderer in Perfume, one of the Bob Dylans in I'm Not There),

and Cornish and Schneider taking top acting honors for 2009. As in Campion's

The Piano, others are party to the central story, and they have identities,

personalities, and claims to intelligence and understanding that we appreciate

without having it announced in dialogue. Kerry Fox (redheaded wild girl

of Campion's An Angel at My Table nearly two decades ago) evokes Fanny's

mother with a few brushstrokes, and Fanny's young sister and brother are

watchful presences and de facto co-conspirators in the courtship. In addition,

Bright Star is the rare period movie to convey—without being insistent—what

it was like to be alive in another era, the nature of houses and rooms

and how people occupied them, the way windows linked spaces and enlarged

people's lives and experiences, how fires warmed as the milky English sunlight

did not. And always there is an aliveness to place and weather, the creak

of boardwalk underfoot and the wind rustling the reeds as lovers walk through

a wetland. Poetry grows from such things; at least, Jane Campion's does.—Richard

T. Jameson

|

.......

Figures of Speech

.

.......The

main figures of speech in the poem are apostrophe and metaphor

in the form of personification. An apostrophe is a figure of speech

in which an author speaks to a person or thing absent or present. A metaphor

is a figure of speech that compares two unlike things without using the

word like, as, or than. Personification is a type

of metaphor that compares an object with a human being. In effect, it treats

an object as a person—hence, the term personification.

Apostrophe and metaphor/personification occur simultaneously in the opening

lines of the poem when Keats addresses the urn as "Thou," "bride,"

"foster-child," and "historian" (apostrophe). In speaking to the urn this

way, he implies that it is a human (metaphor/personification). Keats also

addresses the trees as persons in Stanza 3 and continues to address the

urn as a person in Stanza 5. Other notable figures of speech in the poem

include the following:

Assonance

bride

of quietness, / Thou foster-child

of silence and slow time

Alliteration

Thou foster-child

of silence and slow

time,

/ Sylvan historian,

who canst thus

express

Anaphora

What

men or gods are these? What maidens

loth?

What

mad pursuit? What struggle to escape?

What

pipes and timbrels? What wild ecstasy?

Paradox

What mad pursuit? What struggle

to escape? (The images move even though they

are fixed in marble)

Oxymoron

those [melodies] unheard

peaceful citadel (citadel:

fortress occupied by soldiers)

Study

Questions and Writing Topics

.

1.

Write a romantic ode. The author of a typical romantic ode focused

on a scene, pondered its meaning, and presented a highly personal reaction

to it that included a special insight at the end of the poem (like the

closing lines of “Ode on a Grecian Urn”).

2.

Write a one-stanza poem that imitates the rhyme scheme of "Ode on a Grecian

Urn."

3.

Identify ancient artifacts (perhaps objects that you have seen in a museum)

that would make fitting subjects for poems.

4.

Explain the following lines from the second stanza:

Fair

youth, beneath the trees, thou canst not leave

Thy song, nor ever can those trees be bare;

Bold Lover, never, never canst thou kiss,

Though

winning near the goal—yet, do not grieve;

She cannot fade, though thou hast not thy bliss,

For ever wilt thou love, and she be fair!

|